I saw Esau kissing Kate...

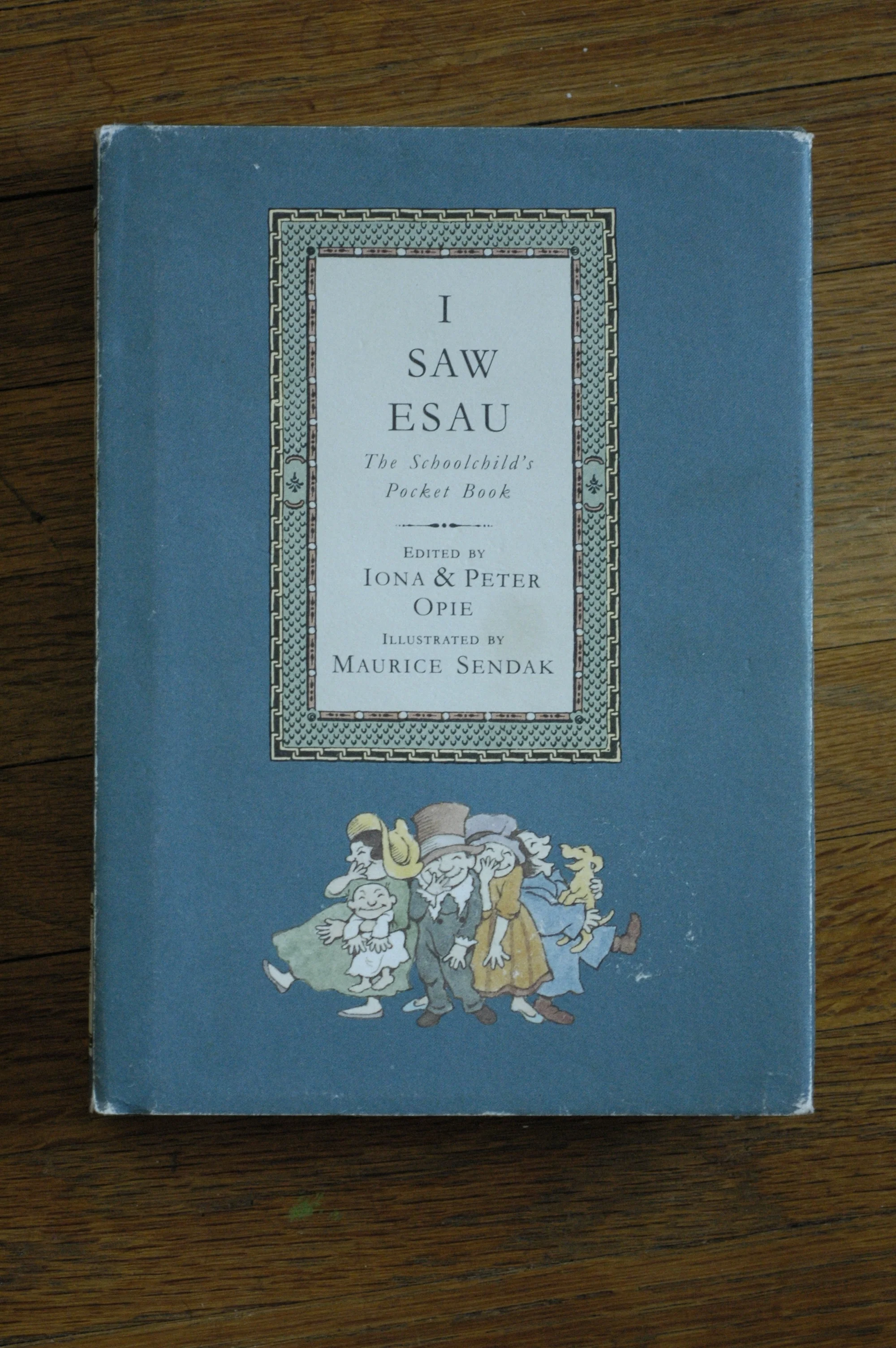

One of my earliest and most memorable experiences of poetry is an old book called I Saw Esau: The Schoolchild's Pocket Book, edited by Iona & Peter Opie and illustrated by Maurice Sendak. I don't know how I came upon it, or how it became a book that I carried with me everywhere, but looking back now I can see that that book is the precise moment when poetry became a part of my life.

I'm sure that my parents bought this book at one point expecting to read it to siblings and me, to entertain us with the rhymes and the characteristic whimsy of Sendak's illustrations, but I eventually claimed it as my own. As Iona Opie explains in the introduction, "Esau was the first book Peter and I produced together. It was a recognition of the particular genius of rhymes that belongs to schoolchildren. They were clearly not rhymes that a grandmother might sing to a grandchild on her knee. They have more oomph and zoom; they pack a punch."

I doubt if I knew what any of the verses meant when I was younger, from the classic "Moses supposes his toeses are roses..." to page 45, riddles like "It is in the rock, but not in the stone..." Most memorable is the title rhyme, "Esau":

I saw Esau kissing Kate,

The fact is we all three saw;

For I saw him,

And he saw me,

And she saw I saw Esau.

I remember saying these short verses again and again, in love with the rhythm, with absolutely no idea that one day I'd be memorizing and reciting the likes of Tennyson and Eliot.

I don't know whether it is just my copy or all of them whose spines are embossed upside down (I like to think that it was a printer's/publisher's joke, considering the nature of the book), but the volume is a joy to behold, some decades after it first became mine. Picking it up today, I can remember what it felt like to hold it in my hands then -- it was surely large and unwieldy for my small frame, but quickly kindling a love for solid and finely-bound hardcovers, and the well-creased jackets that protect them. The pages are thick and crisp, still standing straight and ready to be devoured by eager young schoolchildren like me.

I wish, of course, that I could photograph and share each lilting line, every jaunty illustration.

My mother tells me about, and I vaguely remember, a time when I first became obsessed with words -- I would say everything two or three times, whispering to myself, because I liked the way they felt and sounded coming out of my mouth. A friend recently told me of his son, nearly two years old, who is learning several languages at once. My friend said that it is a wonder to behold the moment when something becomes real because of language: once you find a word for something, it springs into existence. That thing will never be strange or unknown anymore. And with poetry, the elements that become real to us are rhythm, music, sound, motion -- all because of a few well-placed words.

So here's to poetry! Not just for its truth and beauty, but for its playfulness and sense of humor, and its unparalleled ability to shape lives.

It is a help, this book, in our universal predicament. We find we are born, so we might as well stay and do as well as we can, and while we are here we can at least enjoy the endearing absurdities of humankind.

Iona Opie

-- R